As humans prepare to build long-term bases on the Moon and eventually on Mars, most attention naturally focuses on rockets, habitats, and life-support systems. Yet some of the most valuable partners in creating sustainable worlds beyond Earth may be among the smallest creatures we know: insects. Though they cannot play any ecological role aboard the International Space Station, they may become essential to agriculture and recycling in future off-world settlements.

Insects have been part of space research for decades. Fruit flies were the first animals NASA sent into space in 1947, and they have continued to fly regularly as part of the ISS’s biological studies. Their fast life cycle and genetic similarity to humans make them ideal for studying the effects of radiation, immune function, and development in space.

Ants have also been flown to examine how microgravity affects group behavior, while silkworms and butterfly larvae have been used to study development and metamorphosis. In every case, insects had to remain in sealed habitats because microgravity disrupts their ability to orient themselves, walk, or fly. With no gravity to guide their bodies, they become disoriented and drift unpredictably. That makes them valuable research specimens but unsuitable for any ecological role on the ISS.

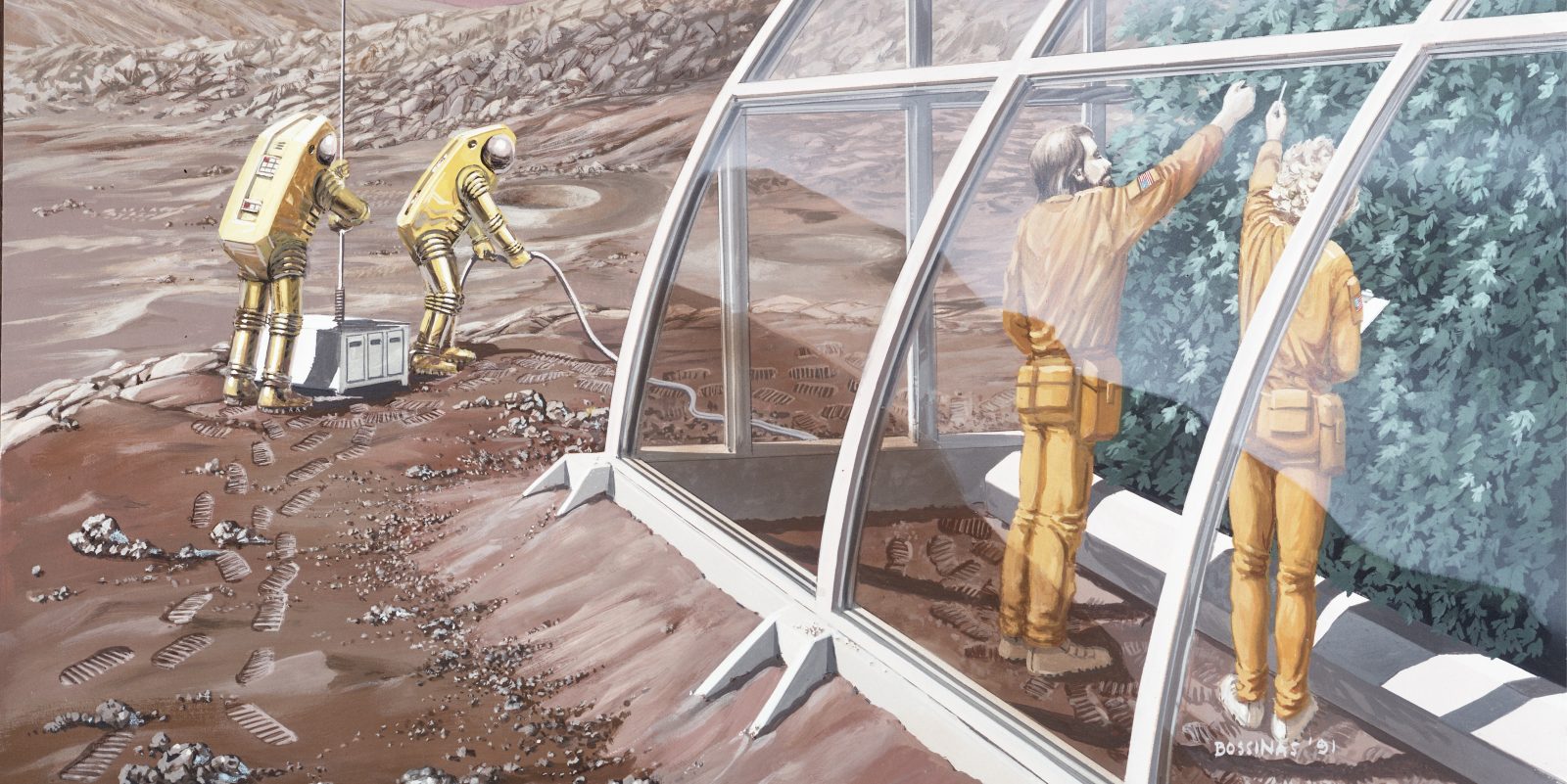

The environments of the Moon and Mars, however, are very different. While the ISS operates in a microgravity environment – essentially in continuous free-fall around our planet – the Moon has about one-sixth of Earth’s gravity, and Mars has a little over one-third. Even this modest pull is enough for insects to regain balance, navigate their surroundings, and carry out natural behaviors more reliably. This opens the possibility that insects could support future food production and recycling systems in ways that are impossible in orbit.

Pollination is one promising example. Early lunar and Martian greenhouses would likely rely on crops such as tomatoes, peppers, strawberries, and leafy greens. Hand-pollinating each flower would be impractical for long-term missions, especially as habitats expand. Bumblebees are strong candidates for off-world pollination. They tolerate confined spaces, adapt well to greenhouse environments, and perform exceptionally well with crops likely to be grown in space. With controlled lighting, airflow, temperature, and humidity, small bumblebee colonies may help sustain reliable harvests far from Earth.

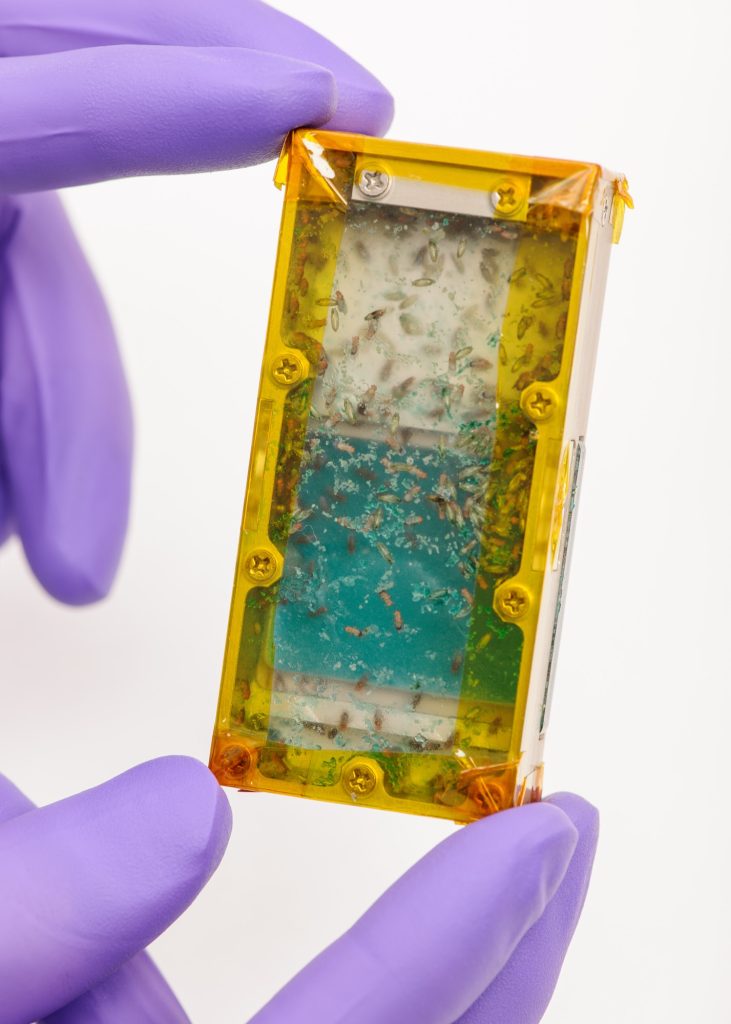

Insects could also play a vital role in closed-loop life-support systems, where every bit of waste must be reused. Black soldier fly larvae can process food scraps quickly, converting them into both fertilizer and high-protein biomass. Mealworms can break down grains, fibers, and some biodegradable materials while producing an edible protein source themselves. Soil-dwelling insects such as springtails and mites help maintain soil structure, aeration, and microbial balance, all key ingredients for healthy plant growth in any regenerative farming system.

These insects would not roam freely through lunar or Martian habitats. Instead, they would likely live inside carefully designed, contained eco-pods that support pollination, soil health, or waste recycling. Together, these miniature ecosystems could provide the biological foundation for sustainable living on other worlds.

For hundreds of millions of years, insects have quietly supported life on Earth. Now, the same species that have traveled to space as research subjects may help us create thriving, self-sustaining communities beyond our planet. In the quest to build new homes on the Moon and Mars, humanity may find its smallest companions are some of its most important partners.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments