No spacecraft returns from orbit the way a commercial airplane descends: all spacecraft returning from orbit must endure a fiery atmospheric reentry, where the atmosphere behaves less like air and more like a blazing barrier of compressed plasma. Spacecraft must meet it with blunt shapes, heat-resistant materials, and aerodynamics designed not for elegance, but for survival during their unpowered descent.

Vehicles like the space shuttle are technically gliding the entire time they are in the atmosphere, but their aerodynamic efficiency is extremely low during the worst of reentry. Understanding why unlocks some of the most ingenious engineering in human spaceflight, from capsules to the shuttle to Starship.

Riding the shockwave

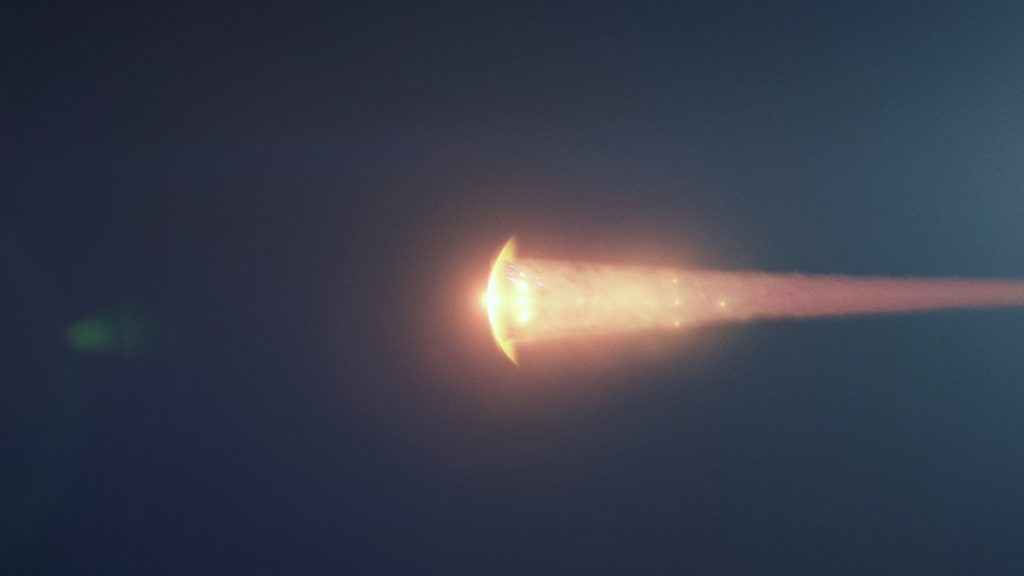

When a vehicle reenters the atmosphere, it slams into air so fast the molecules in front of it compress into plasma thousands of degrees hotter than the vehicle itself can tolerate. Survival depends on creating a detached shockwave – a bubble of superheated gas that stands off from the vehicle’s body. This separation lowers the heat that actually reaches the skin of the spacecraft.

Only blunt, wide surfaces can do this effectively. That’s why capsules like Apollo, Orion, and Crew Dragon are shaped like shallow bowls. Their geometry pushes the shockwave outward, spreading heat over a large area and reducing thermal stress. A pointed or narrow body would force the shockwave to cling tightly to the structure, delivering catastrophic heat directly to the skin.

This is also why meteors break apart. Most are brittle stone or metal entering at steep angles with no stabilization. They tumble violently, endure attached shockwaves, and shatter under combined thermal and aerodynamic forces. A spacecraft, by contrast, enters at a controlled angle, maintains a stable orientation, and uses engineered materials that channel heat away predictably.

Capsules: Simple, stable, shock-resistant

Capsules may seem like simple “falling pods,” but their design is deliberate and sophisticated. Their center of mass is intentionally offset, giving them the ability to generate lift without wings. That lift, although minimal, allows them to steer, bleed off g-loads more gradually, and shift their trajectory by hundreds of miles.

Ablative heat shields carry away heat by slowly charring and shedding layers, sacrificing material to protect the crew. This proven design is one reason capsules have remained the gold standard for high-energy Earth reentry.

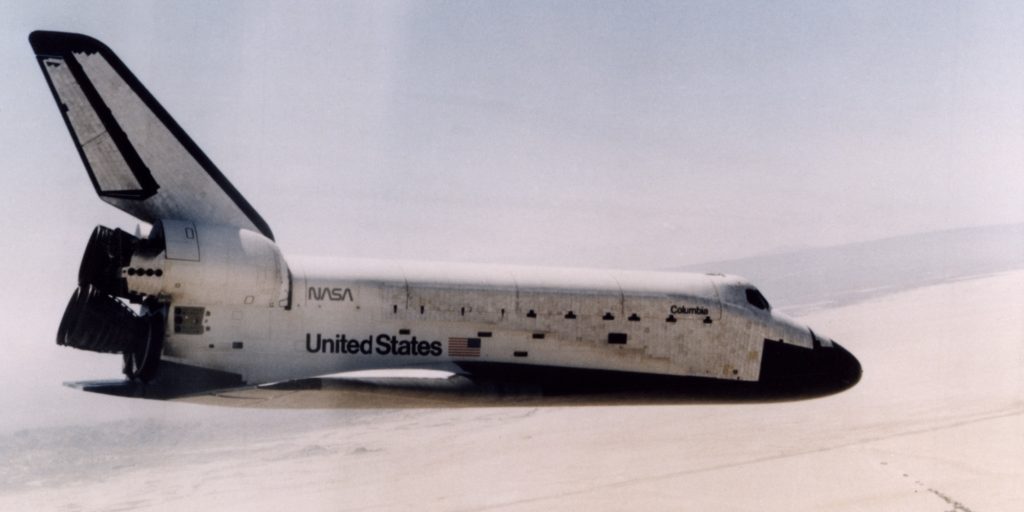

An unpowered orbiter shaped for survival first, flight efficiency second

The space shuttle is often imagined as an airplane that flew from space, but its design reveals something different. Its nose was intentionally blunt, not sharp, to force a detached shockwave. Its enormous belly was covered with silica tiles that insulated against 3,000-degree plasma while radiating heat outward.

During the hottest portion of entry, the shuttle flew at a steep angle of attack that maximized drag and limited lift, making its wings behave less like airplane wings and more like aerodynamic brakes, yet still producing enough lift for controlled banking flight from the very start of atmospheric entry.

The shuttle was always an unpowered glider once it entered the atmosphere. However, its aerodynamic efficiency was very poor at hypersonic speeds, improving continuously as it decelerated from hypersonic, to supersonic, to subsonic flight. Even then, it flew steep, high-sink-rate approaches that resembled a controlled dive rather than a gentle landing.

Lifting bodies: The middle path

Vehicles like NASA’s HL-20 concept and Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser represent a hybrid approach. Their fuselages generate lift through their shape, functioning as lifting bodies rather than traditional winged aircraft. They survive reentry with blunt, heat-resistant surfaces like a capsule but provide enough aerodynamic control to land on runways.

Starship and the belly flop revolution

SpaceX’s Starship takes a different approach altogether. It enters broadside, performing a dramatic “belly flop” that maximizes drag, drastically slows the vehicle, and spreads heating over the largest possible area.

Its four flaps adjust the vehicle’s orientation much like a skydiver altering body position, giving Starship active control throughout hypersonic, supersonic and subsonic descent. Its stainless steel structure tolerates higher temperatures than aluminum, while thousands of black ceramic tiles insulate the steel structure from intense heating.

Only after Starship slows through hypersonic and supersonic regimes does it flip upright and land with its engines.

Falcon 9: The engine-first reentry

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 boosters use yet another method. Instead of broadside or belly-first, Falcon 9 turns completely around and enters engine-first.

During descent, the thick engine section and octaweb absorb the worst of the heating while a short “entry burn” creates a cushion of exhaust that slows the booster while reducing plasma heating that reaches the structure. This is called supersonic retropropulsion. Grid fins then steer the rocket as it descends.

This unique strategy is one reason the Falcon 9 remains the world’s first and most reliable reusable orbital-class booster.

Recently Blue Origin has joined the club with the success of its second New Glenn rocket launch and booster landing on its droneship.

The plasma blackout: When spacecraft fall silent

During reentry, spacecraft often lose radio contact for several minutes. This blackout happens when the plasma sheath surrounding the vehicle becomes so dense that it blocks radio waves.

Apollo missions experienced long blackouts. SpaceX vehicles sometimes shorten or avoid them due to advanced antennas and shallow entry angles. Starship is being designed to maintain communication even through heavy plasma, potentially ending blackout periods entirely.

Managing unpowered flight through reentry

The common thread across all designs is this: all returning spacecraft must survive reentry through careful management of heat, shockwaves, and stability. While some are technically always in a glide, they only achieve the aerodynamic efficiency that resembles flight in a traditional sense after the atmosphere becomes thick and slow enough. And capsules generate only modest lift – enough to steer but not enough to sustain flight.

Space isn’t just cold and empty. Coming home from it requires meeting Earth head-on, managing forces that would tear apart anything shaped like a traditional aircraft. Heat shields, tiles, lifting bodies, and belly flops are humanity’s ingenious answers to the most violent journey any vehicle can make.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments