As the International Space Station approaches the end of its operational life later this decade, low Earth orbit is entering a transition that may be just as consequential as the station’s original construction. NASA has made clear that, rather than replacing the ISS with another government-owned outpost, it intends to purchase services from commercially owned space stations, freeing the agency to focus its resources on deep space exploration and the Artemis program.

That shift has opened the door to a new generation of private companies proposing alternatives to the ISS model. Among them is Max Space, a Florida-based startup operating near Kennedy Space Center. The company is pursuing a challenging but conceptually simple idea: expandable space habitats that launch compactly and then deploy in orbit to create far more usable pressurized volume than traditional rigid modules.

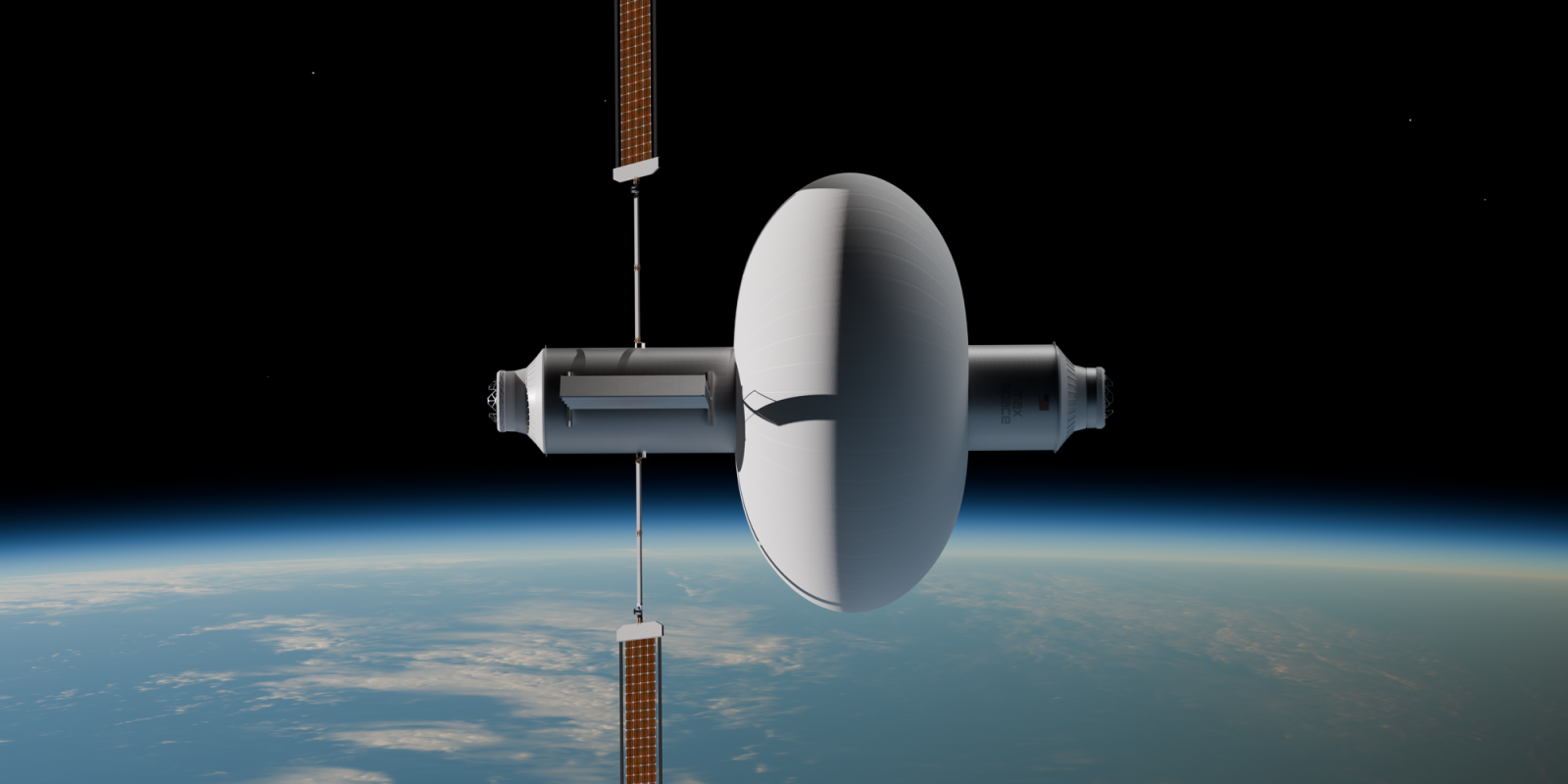

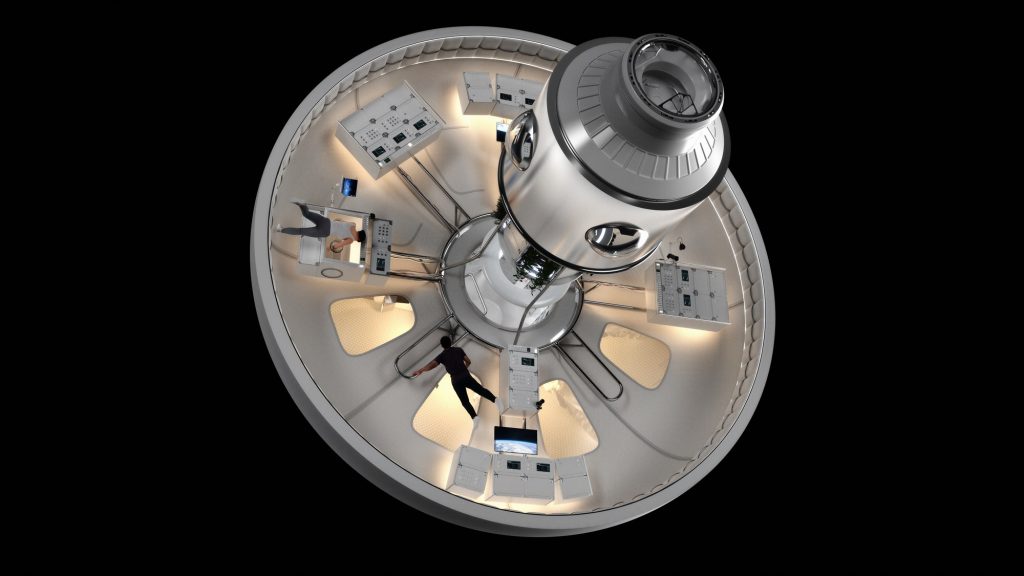

The company’s flagship concept, Thunderbird, is being designed as a single-launch commercial habitat for low Earth orbit. Unlike the ISS, which required dozens of shuttle and rocket flights and years of on-orbit assembly, Thunderbird would expand after launch into a large, human-rated environment suitable for research, in-space manufacturing, crewed missions, and private use.

Expandable, fabric-based structures allow designers to maximize volume while staying within the mass and size limits of current launch vehicles. NASA has previously tested inflatable modules in orbit, demonstrating that layered “soft-goods” structures can provide effective protection against micrometeoroids, radiation, and pressure loss. Max Space’s aim is to scale that heritage into a standalone destination rather than an auxiliary module. If successful, this could significantly reduce the cost and complexity of maintaining a human presence in orbit.

Max Space is still early in its lifecycle. The company is working with NASA through Space Act Agreements, which allow technical collaboration without committing the agency to a full procurement contract. It has also announced plans to launch Thunderbird aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket later this decade, with smaller demonstration missions planned beforehand to validate deployment and systems performance.

The leadership team reflects a mix of entrepreneurial and technical pedigree. Max Space was co-founded by CEO Saleem Miyan, Chairman Aaron Kemmer, and Chief Technology Officer Maxim de Jong, the latter bringing deep experience in expandable habitat architecture. The company has also emphasized crew-centric design, enlisting former NASA astronaut Nicole Stott to help shape the interior around real operational needs in microgravity rather than purely conceptual layouts.

Public information about Max Space’s funding remains limited. The company appears to be operating on early-stage private capital rather than large institutional backing, a contrast to some higher-profile competitors pursuing rigid-module stations or luxury-oriented orbital platforms. That quieter posture may be intentional, allowing the company to focus on engineering validation rather than rapid scale-up.

The Artemis connection is subtle but important. As NASA shifts its human exploration efforts toward the Moon and eventually Mars, it still requires reliable, flexible infrastructure in low Earth orbit for crew training, research, and technology maturation. Commercial stations are expected to absorb much of that role after ISS retirement in 2030. In that context, expandable habitats like Thunderbird could offer a cost-effective way to provide large volumes for long-duration missions, life-support testing, and in-space manufacturing, all of which feed forward into deep space exploration.

Max Space is not the loudest voice in the commercial station race, but its approach highlights a broader trend of the post-ISS era: the next generation of orbital infrastructure may look very different from the station that defined the last quarter-century. If expandable habitats can be proven at scale, they could reshape how orbital real estate is built, launched, and sustained, just as NASA turns its gaze outward toward the Moon and beyond.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments