Falcon 9

Falcon 9 is a reusable, two-stage rocket designed and manufactured by SpaceX. It is the world's very first orbital-class reusable rocket.

Table of contents

- The worlds first reusable orbital-class rocket

- Falcon 9 variants

- Falcon 9 Reusability FAQ

- Why doesn’t SpaceX use parachutes?

- What are the white spots and lines on reused Falcon 9 boosters?

- Why does SpaceX use droneships to land Falcon 9 boosters? Why not return to land?

- Why don’t other rocket companies reuse their boosters?

- How are these Boosters numbered?

- How many times can a Falcon 9 booster launch?

The worlds first reusable orbital-class rocket

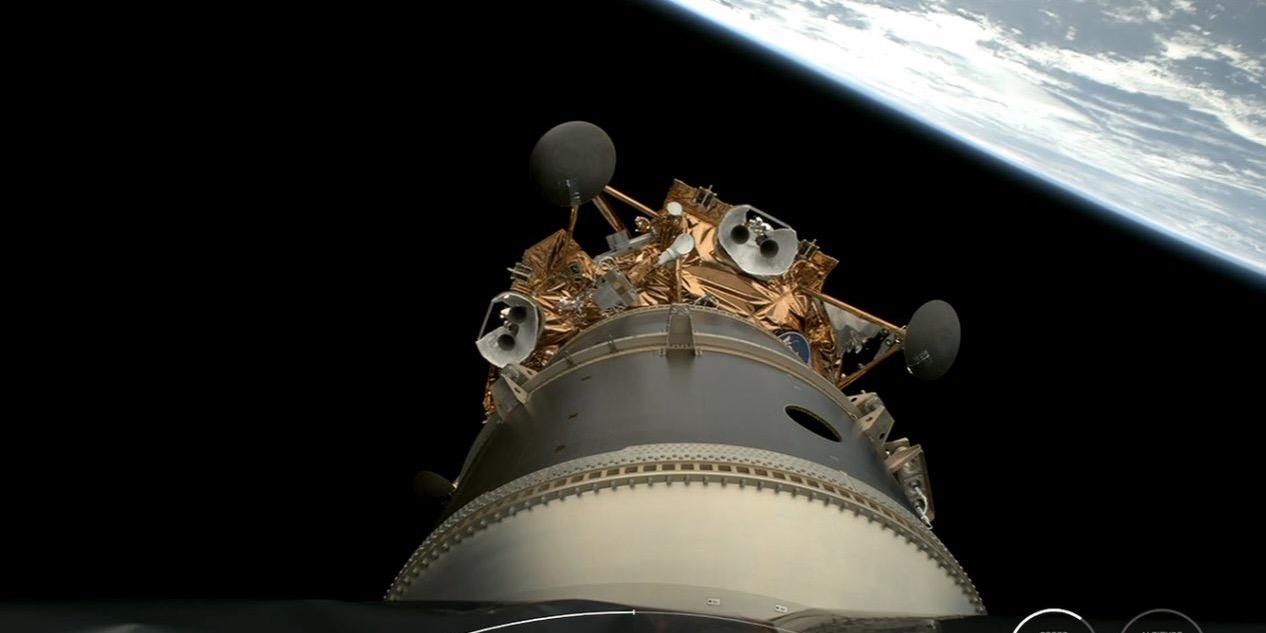

The Falcon 9 is a two-stage, reusable medium lift orbital rocket designed and manufactured by SpaceX. It has the honor of holding the title of “First reusable orbital rocket.” Because of it innovation in reusable technology, SpaceX has been able take a firm grasp on the commercial launch sector, becoming a near, de facto monopoly for access to space.

Falcon 9 comes in at 229.6 fee tall and a mass of 1.2 million pounds. Its first stage, often called the booster, is powered by nine Merlin engines that can generate 1.3 million pounds of thrust at sea level and 1.5 million pounds of thrust when the rocket reaches the vacuum of space. Its second stage is powered by a single, vacuum optimized version of the Merlin engine.

SpaceX has two options for the second stage Merlin’s engine bell: a standard, full size bell and a cheaper, stubbier bell that is easier and faster to produce. SpaceX offers this bell to missions that don’t require the engines full capability to further lower the cost.

The Falcon 9’s payload fairing is the standard 5.2 meters or about ~17 feet wide and can easier fit a school bus inside. These fairings are also reusable. Both halves sport attitude control thrusters and storable parachutes that allow for a targeted splashdown at sea.

As of January 2025, SpaceX has launched the Falcon 9 428 times with only two failures and one partial failure. The Falcon 9 also suffered a loss of the rocket and payload in a preflight static fire back in 2016.

Falcon 9 variants

SpaceX built five different versions of the Falcon 9 since it became operational in 2010: v1.0, v1.1, Full Thrust, an interim Block 4, and its final form of Block 5. Each variant made slight changes that increased the rocket’s performance and reusability. Making it one of the most flown and reliable rockets ever.

Falcon 9 v1.0

Built to fulfill SpaceX’s contract with NASA to launch cargo resupply missions to the International Space Station, the Falcon 9 v1.0 was the shortest and least capable version of the Falcon 9 family. All five of its flights flew the Dragon v1 cargo spacecraft, with three of them rendezvousing and berthing with the ISS.

The first stage was powered by nine Merlin 1C engines and was arranged in a 3×3 configuration. The upper stage was powered by a single Merlin 1C engine. In total, it came in at about 55 meters tall and could lift 9,000 kg into low Earth orbit.

SpaceX was already considering reusability with the v1.0 Falcon 9s, testing ocean landings with parachutes during descent. None of the attempts were successful, however.

the v1.0’s first launch took place on June 4, 2010, and its final flight was on March 1, 2013. Given that they are expendable rockets, no version of the v1.0 is on display today.

Falcon 9 v1.1

Falcon 9 Full Thrust

Falcon 9 Block 4

Falcon 9 Block 5

Falcon 9 Reusability FAQ

Why doesn’t SpaceX use parachutes?

This question is a bit more complicated, so we wrote a whole article on it.

What are the white spots and lines on reused Falcon 9 boosters?

The spots and lines that appear lighter on the boosters after flight are where SpaceX cleans the boosters for inspections between launches. They focus on inspecting the welds, so they clean those areas to ensure the booster is safe and ready for the next flight but they don’t clean the rest of the booster.

Why do Falcon 9 boosters get darker every flight?

During descent, in addition to a large amount of heat generated, a Falcon 9 flies through its own exhaust during the reentry and landing burns. This deposits soot onto the sides of the booster while the legs, in their folded position, create a clean outline where the soot cannot reach.

Why doesn’t SpaceX clean the Falcon 9 boosters?

Simply put, it is extremely costly and delays the re-flight of a booster without providing any tangible benefit. With SpaceX sometimes reusing boosters less than a month after a previous launch, those delays are costly. Likewise, using harsh chemicals or even just directly spraying boosters with water is not ideal. It doesn’t take much to cause issues. In 2020, a small piece of masking lacquer in a Merlin engine caused an engine issue that delayed multiple launches as they investigated the problem, so any risks should be avoided. Besides, just as predicted this dirtier style has truly become a space-fan favorite.

Why does SpaceX use droneships to land Falcon 9 boosters? Why not return to land?

Landing boosters on droneships saves a great deal of fuel and increases the possible payload the booster can carry to orbit. When landing on a drone ship, the booster can continue on its trajectory and land a few hundred kilometers out into the ocean, but for a return to the launch site, the booster needs an additional boost back burn to cancel the horizontal velocity and return back to land. Depending on the payload size and flight profile of the rocket determines if SpaceX can land its boosters on land or require a droneship.

However, SpaceX is still learning in this area when it comes to launches. When SpaceX began launching its Dragon 2 capsule neither its crewed nor cargo variants could land back on land. However, after a decade plus of flight experiences and always trying to improve the rocket’s performance, SpaceX found a profile for both crewed and cargo Dragon 2 flights to return to LZ-1.

Why don’t other rocket companies reuse their boosters?

Reusing boosters is expensive and potentially risky. There is an added degree of complexity that comes with the reuse of boosters. SpaceX has an array of chartered vessels to safely return boosters, fairings, and Dragon capsules back to port which all cost money. Reusing boosters also decrease the payload to orbit of a rocket. Any fuel that needs to be used for landing is then not able to be used to accelerate the payloads.

SpaceX also follows a far different design and testing philosophy from companies like ULA. SpaceX will take many risks and fail many times over in order to develop and progress quickly; just look at Starship. ULA, on the other hand, tends to work slower and more conservatively in an attempt to ensure success and at the first launch. Reusing a rocket includes an inherent risk of failure, especially on a first attempt. According to Tory Bruno’s estimate, they would need to fly a booster 10 times in order for it to be financially justified. This is far off from the two flights that SpaceX claims they need, but even so, SpaceX has far surpassed that 10 flight number. SpaceX’s current reflight record is 25 flights.

Even with these challenges, more rocket companies are quickly moving towards reuse. ULA has the “SMART reuse” for their upcoming Vulcan rocket. Rocket Lab is a great example of a company modifying its existing rocket design for reusability, although that isn’t always possible. Rocket Lab’s next rocket, Neutron, will have reusability in mind from the start. Relativity is another company that will have reusability in mind when developing its Terran R vehicle.

How are these Boosters numbered?

Falcon 9 Boosters are numbered with a B followed by a four-digit number. The original V1.0 boosters started with B0000, but after the first seven they moved to B1001 and count up sequentially from there. There is a second number that follows the booster number, which is often used to designate the launch number. This is separated by either a period or a hyphen. Internally, SpaceX uses a hyphen to designate this launch number.

The final two digits of the booster number are placed on the boosters. They are visible both near the Falcon 9 logo at the top of the booster and on newer boosters, the logo is also placed between the legs of the booster. Here the “51” can be seen as B1051-10 returned to port.

As you can see these numbers are painted in black so as the booster is used more and more, it becomes difficult to tell what booster they are.

How many times can a Falcon 9 booster launch?

Simply put, SpaceX doesn’t know. Originally thought to be 10 reuses, the amount of degradation was far less than expected and Elon has speculated that they could reach 100 launches of an individual booster. With more reuse means there will need to be more refurbishment, but SpaceX plans to continue pushing the life-leading boosters to their limits with the growing number of Starlink launches, where only their own payloads are at risk of a launch failure. Currently, booster B1067 is the life-leading booster, having flown 25 launches, starting with CRS-22 in June of 2021 and most recently supporting the Starlink Group 12-12 mission in January of 2025.